Smart subsidies and digital innovation: Lessons from Togo’s off-grid solar subsidy scheme

This blog is the first of a two-part series.

Mobile money-enabled digital payments have become central to the off-grid energy sector – particularly due to the rapid expansion of pay-as-you-go (PAYG) solar-home-systems throughout many African countries. In 2019, 2.19 million PAYG devices were sold globally [1], and PAYG solar providers captured 91 per cent of the $500 million invested in the off-grid energy sector in 2018. [2]

Digital payments allow unbanked customers to flexibly pay for energy services remotely and securely. Energy access providers can scale their operations more rapidly due to lower costs of payment collection with digital payments and greater assurance of payment with locking technology. They’re also able to monitor customer consumption dynamics, tailor their repayment plans and product offerings to evolving repayment patters and estimated energy demand, and leverage payment histories to identify customers for upselling.

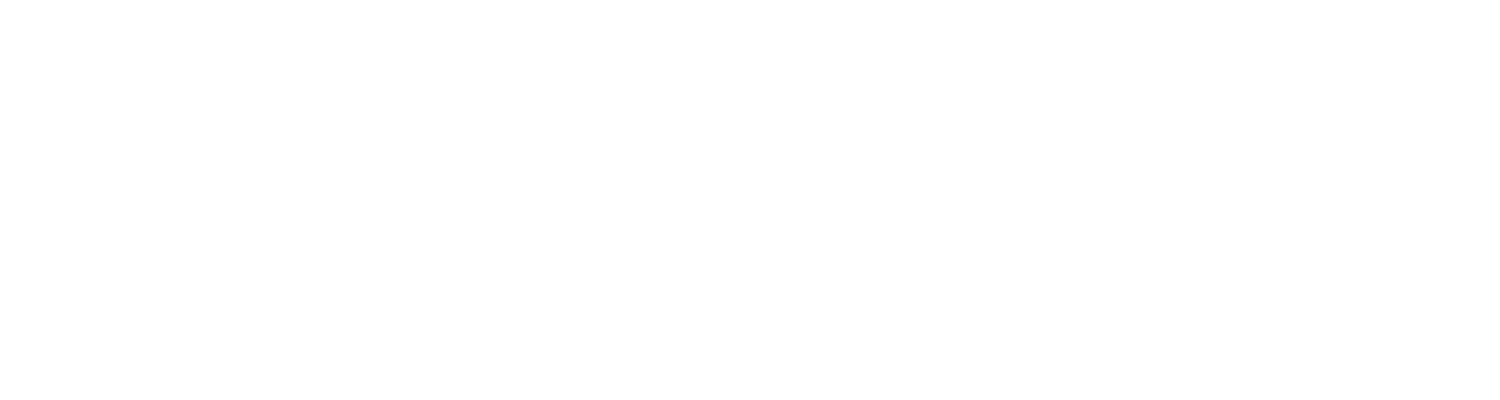

The wider digitalisation of the sector and the emergence of other tools have also had important benefits to energy access providers, investors, governments, and donors:

Source: TFE Energy – Energy Access Data and Digital Solutions (2019)

While digitalisation has mainly benefitted companies in the off-grid energy sector, governments and their rural electrification agencies are becoming increasingly sophisticated in leveraging digital tools to meet their development and public policy objectives. For example, there’s been increasing use of geospatial analysis to predict energy demand among settlements over time, in order to effectively identify the least-cost and most suitable electrification technology (grid extension, mini-grids, or solar-home-systems) for a given settlement. This is a key enabler of integrated energy planning initiatives being pioneered in Togo, as well as Nigeria through the Nigeria Electrification Project implemented by the Rural Electrification Agency of Nigeria. Increasingly, digital tools are also being leveraged to scale up renewable energy up-take among rural low-income populations through smart subsidies. This blog will consider the role of digital innovations in Togo’s subsidy scheme for rural electrification, and explore the role of partnerships between private service providers, mobile operators and government. In doing so, we identify potential lessons for other countries aiming to accelerate the uptake of off-grid solar services.

Introducing Togo’s CIZO programme

In the off-grid energy sector, governments and donors throughout low-and-middle income countries – including Kenya, Zambia, Nigeria, and Rwanda – have recently piloted or launched a range of demand-side subsidy programmes to accelerate universal energy access, as well as meeting national development objectives.

The CIZO programme, launched by the government of Togo in 2017, stands out as one of the most ambitious and interesting examples of government leveraging digital tools to rapidly and effectively increase energy access through the uptake of off-grid energy services. Though Togo’s energy access rate already improved rapidly over the past decade (31 per cent in 2010 to 51 per cent in 2018 [3]), rural energy access remains low at 22.4 per cent as of 2018. Through CIZO, the government of Togo aims to tackle this challenge, and accelerate the extension of energy services in rural areas.

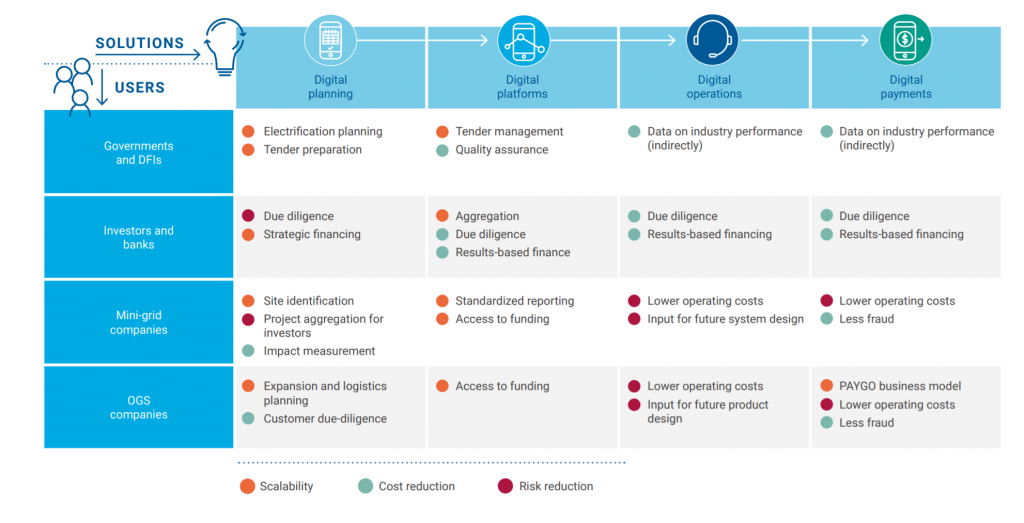

The Government of Togo has designed an electrification strategy using geospatial modelling to assess the most efficient means of electrifying selected rural households. The strategy covers the deployment of 555,000 Solar Home System (SHS) (CIZO programme), 300 mini-grids (55,000 connections), and 400,000 on-grid connections between 2018 and 2030 with the ultimate aim of reaching universal electrification by 2030. [4]

Here, we will focus mainly on the CIZO SHS subsidy programme, which has already displayed some significant achievements.

Source: Lighting Global, Togo Electrification Strategy

The programme is implemented in collaboration with a range of authorised PAYG solar companies, which to date include: BBOXX (under a joint-venture between BBOXX and French energy provider EDF), Soleva, Fenix (now Engie Energy Access), Solergie, and Moon. The figure above outlines the stages of deployment for CIZO. Licenses are granted based on:

- Service and after-sales service quality over the long term;

- Preference for the energy as a service model, rather than a loan to ownership model;

- Minimum 20W with the option to upgrade for all operators;

- Minimum product quality (min. Lighting Global certification); and

- Machine to machine connectivity (M2M) with the option to connect to a national platform. [5]

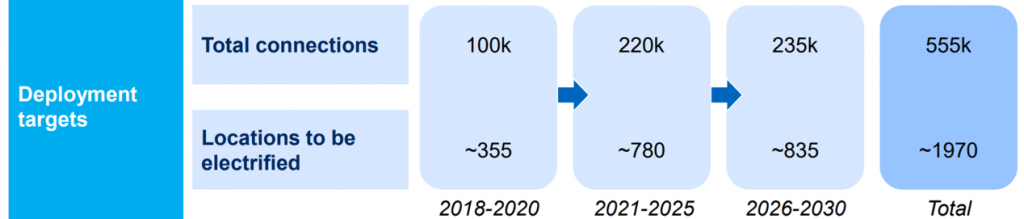

These private sector partners are responsible for operations along the value chain (e.g. kit purchase, distribution, payment collection, maintenance), while the public sector provides subsidised access, consumer awareness campaigns, and VAT exemptions. For instance, private operator costs are cut through preferential tariffs (-20 per cent) in case: state logistics are used (the national postal agency LaPoste providing transport, and warehousing services), state-sponsored marketing campaigns, and the training of local agents in maintenance via solar academies and customers in SHS usage.

Notes (1) = Technical assistance and indirect support; (2) = financial instruments; (3) = Public investment

Source: Lighting Global, Togo Electrification Strategy

With the subsidy, dubbed the ‘CIZO Cheque’, households with SHSs from authorised providers are able to access a monthly subsidy of 2,000 FCFA (c.4$) for the SHS payment plan over a three-year period. Every rural customer is eligible for the subsidy. [6] Mobile operators such as Togo Cellulaire and Moov, and their respective mobile money services T Money and Flooz, are key enablers and partners of the government and SHS providers. Private service providers collect customer information, which is aggregated by their mobile operator partners and LaPoste to establish an integrated national platform for all eligible customers. In our recent webinar on the future of pay-as-you-go partnerships, Andrew Kent a Product Manager at BBOXX, described the process: “BBOXX customers make a payment through mobile money, the mobile operator checks if the customer qualifies for the subsidy, and then tops up the customer’s payment with the subsidy before sending it to BBOXX.” The scheme allows private sector partners to verify energy consumption and payments via M2M and report to the rural electrification agency (AT2ER) as proof that key performance targets and specified priorities are being met.

Key to the ease of implementation of the programme is companies’ ability to monitor consumer consumption. As Ajadi Bakari Shegun, Presidential adviser in charge of this programme pointed out at the GOGLA end-user subsidy conference, the programme’s success depends on leveraging digital tools. They lower the operational cost of the programme, and allow the government to ensure that subsidies are used explicitly for its intended purpose: the remote verification of new installations, and of monthly subsidy uptake. Shegun also pointed out that the government did not want to provide completely free access, as some form of payment is key for the programme’s long-term sustainability. He stressed that despite the significant costs of the programme for a low-income country such as Togo with a poverty rate of 53.5 per cent as of 2017, “end-user subsidies are not a waste of money, they increase energy access, help build the tax base and create jobs. They are an investment in the economy.” This is one of the key reasons for wide-ranging subsidy eligibility, as in the long-term, Shegun argues, raising energy demand among rural households will induce a virtuous cycle, and also make the country more attractive to other DESCOs.

Looking forward

As Cina Lawson, Togo’s Minister of Posts, Digital Economy, and Technological Innovation, stresses, the benefits of data collected via M2M goes beyond the effectiveness of the current programme. They allow the country to generate insights that can subsequently promote the development of other products and services for rural populations. In a recent blog, Lawson, pointed out that the country will soon pilot a unified open-source platform connecting consumers to providers of PAYG goods and services. The platform aims to open up opportunities for other companies interested in delivering goods and services to rural populations the ability to manage equipment remotely, centralized access to data on customer expenditure (in turn providing credit history access), and access to a secure mobile payment processing system.

BBOXX and EDF have also recently announced a new partnership with solar water pump provider and GSMA Digital Utilities Innovation Fund grantee SunCulture, which will be deploying subsidised water pumps to raise agricultural productivity among rural farmers. Similarly, to the CIZO cheque for off-grid energy access, the government will be providing a 50 per cent to halve the cost of solar-powered farming and irrigation systems for 5,000 farmers, as well as tax exemptions on import duties and VAT on the water pumps. [7]

In the longer term, the Government of Togo plans to integrate the CIZO scheme under a national electrification fund, which will also seek to include grid connections and mini-grids, while providing access to finance for smart meters.

Togo sees subsidising electrification as a long-term investment, which will provide the government with important data points about the evolution of well-being of households supported through the scheme, while also opening up opportunities for domestic resource mobilisation.

Subsidy programmes and digitalisation – a virtuous cycle?

Mobile penetration in Togo has been growing rapidly prior to the introduction of CIZO with the country’s unique mobile subscriber penetration rate increasing from 38.7 per cent in 2015 to 48.5 per cent in 2020 according to GSMA Intelligence. In terms of connectivity, 66 per cent of the population are covered by 3G [8], while over 95 per cent are estimated to be covered by 2G. [9]

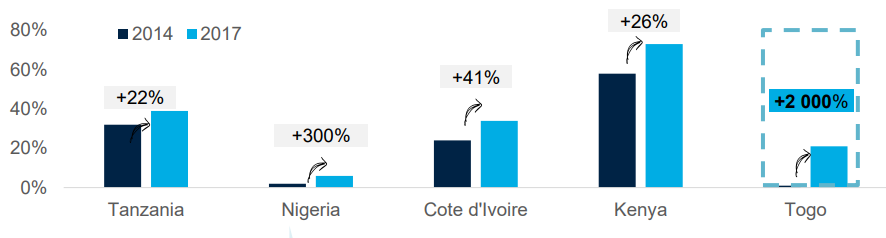

The growth of mobile penetration and connectivity, along with the country’s maturing mobile money landscape, is not only critical for the scaling of pay-as-you-go solar services throughout the country, but also for the implementation of the subsidy scheme. According to the PAYGO Market Attractiveness Index, which ranks several low- and middle-income countries, Togo ranks seventh – partly due to its rapidly increasing access and use of mobile money. [10] Togo’s high financial inclusion rate at 45 per cent exceeds regional counter parts such as Senegal (42 per cent), Cote d’Ivoire (41 per cent) and Benin (38 per cent).[11] Between 2015 and 2017, the percentage of customers with a mobile money account increased from 1 per cent in 2015 to 21 per cent in 2017 (see figure below) [12], being the main driver of increased financial inclusion in the country.

Percentage of adult population having a mobile money account

Source: IFC (2018), Off-Grid Solar Market Research for Togo

This trend has been accelerated by the government’s wider digitalisation strategy. It includes providing cash transfers to recipients of various social programs via digital payments, with 49 per cent receiving government payments into a financial institution account, and 30 per cent of recipients opening their first account to receive their payment. [13]

Most recently in response to COVID-19, the government unveiled Novissi, a social welfare programme using digital cash transfers with the aim of helping informal workers whose livelihoods had been disrupted by the pandemic and the accompanying lockdown. [14] The government partnered with Joshua Blumenstock from UC Berkeley’s Center for Effective Global Action, and the NGO GiveDirectly to rapidly but effectively target eligible programme recipients using mobile and satellite data.

In Togo, social transfer programmes whether in the form of cash transfers such as Novissi or in the form of subsidies such as CIZO not only focus on effectively providing support in the short term, but also aim to support the government’s longer-term digitisation agenda. Togo’s Digital Economy Strategy explicitly mentions the CIZO scheme, as there are important interaction effects between rural electrification and driving digital connectivity. As our recent multi-country study on the value of PAYG for mobile operators highlighted, PAYG adoption drives mobile money adoption with 20 – 30 per cent of new PAYG clients in our study registering or reactivating mobile money accounts and data usage among PAYG clients in our study being significantly higher than the control group.

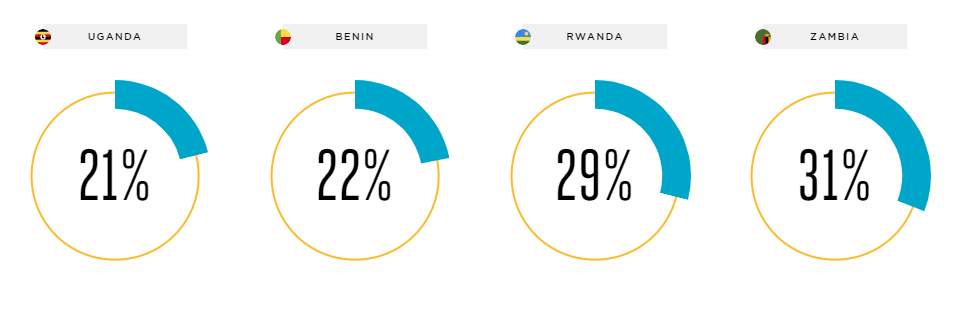

Proportion of PAYG customers that newly subscribed to, or re-activated, their mobile money account with selected MNO

Source: GSMA (2020) The Value of PAYG for Mobile Operators

It will be interesting to study the impact of CIZO on increased mobile money penetration, average revenue per user (ARPU), and mobile money agent income/penetration in rural areas.

What can other countries learn from Togo’s programme?

What is interesting about the Togo programme is that given the “nascency of the off-grid solar sector in the country, the Togolese Government launched the CIZO project to utilise all the interventions at the same time.” [15] Subsidy schemes in energy access usually differentiate between:

- Enabling environment interventions such as VAT exemptions, preferential access to government distribution networks.

- Supply-side subsidies such as grants of results-based financing to lower cost of reaching low-income households for service providers.

- End-user subsidies for example schemes directly targeting customers such as cash transfers or vouchers. [16]

Other countries aiming to launch similar initiatives and catalyse the expansion of off-grid solar services among low-income populations should consider the benefits of such a holistic approach. One example is the Democratic Republic of Congo, where 79.2 million people lack access to electricity – the highest amount of people without access to electricity in any country globally. It recently established a rural and peri-urban electrification agency ANSER and announced a subsidy scheme Fonds Mwinda to double to the energy access rate (currently at 8.7 per cent) from now until 2024.

While innovations and business models in off-grid solar have made energy services more accessible and cheaper for low-income rural populations in countries like the DRC and Togo, the affordability challenge remains paramount. With 72 per cent of its population living on less than $1.90 a day, a significant proportion of the DRC’s rural population simply can not afford most payment plans for SHSs that support a basic set of appliances without a subsidy. Meanwhile, most grid extension programmes in low- and middle-income countries requireinvestments of $1,500 per connection or more with 70 – 100 per cent of these costs covered by subsidies. Introducing supply-side and enabling environment interventions alongside end-user subsidies not only makes off-grid solar accessible to a greater proportion of the population, but also levels the playing field and lowers operational costs for off-grid energy service providers with a proven capability of reaching lower-income, rural populations. It also supports states in maximizing the welfare gains from public finances allocated to energy subsidies, and enables integrated electrification strategies, which take into account the evolution of affordability and energy demand. At the same time, it is critical that innovative subsidy and integrated electrification strategies are enabled by and reinforce wider digitalisation strategies, as the absence of mobile connectivity and mobile money make such schemes far more difficult to operate at scale. From a political economy perspective, CIZO seems able to overcome some of the coordination and policy fragmentation constraints plaguing other subsidy schemes due to leadership and buy-in at the presidential level, and high-level public sector champions such as Lawson and Shegun. Of course, we’re excited to learn more about the programme’s effectiveness over the coming years, as it’s still too early to draw conclusive insights.

[1] GOGLA (2019), Global Off-Grid Solar Market Report [2] Wood Mackenzie (2019), Strategic investments in energy access [3] World Bank Development Indicators [4] GOGLA (2020), Demand-Side Subsidies in Off-Grid Solar [5] Lighting Global (2018), Togo Electrification Strategy [6] BBOXX (2019), Bboxx receives a first-ever government subsidy [7] ESI Africa (2020), Partnership cultivated to deliver solar-powered farming in Togo [8] GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index (2020) [9] IFC (2018), Off-Grid Solar Market Research for Togo [10] IFC (2019), PAYGo Market Attractiveness Index 2019 [11] Microsave (2020), Inclusive Fintechs in Francophone West Africa [12] World Bank (2019), World Bank Lighting Global [13] Microsave, Inclusive Fintechs in Francophone West Africa [14] Quartz Africa (2020), Digital platforms have been a boon for social assistance in African countries during the pandemic [15] GOGLA (2020), Demand-Side Subsidies in Off-Grid Solar [16] PV Magazine (2021), How end-user subsidies can help achieve universal energy accessThe GSMA Digital Utilities programme is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), and supported by the GSMA and its members.

Source : GSMA